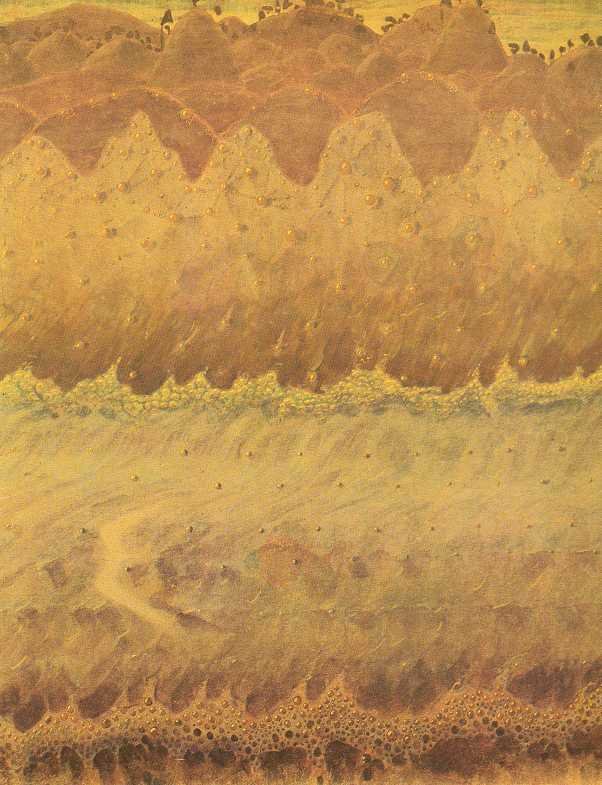

Odilon Redon, Underwater Vision, c. 1904

“Swaying mesmerically in the overheated water the immense golden petals of the giant aquatic rose held the drowned landscape spellbound. I’d journeyed far to see this, this monstrous deity blooming at the secret heart of an impossible undersea world. As I gazed into the lush recessive folds of the flower’s central core it emitted a deep-bass drone, the sound pulsing outward through the warm amniotic water, reverberating out across the sunken regions of the now collapsing dream.”

An excerpt from my text The Deep Well, published in issue two of MIA Journal, appearing among a collection of writings by artists united by a shared enthusiasm for nature and landscape. The full piece is online here.

Odilon Redon, Seahorses on a Underwater Scape, 1909

Immersion

In this communiqué I have decided to present some of the aquatic imagery that inspires me, rather than writing the usual series of short, thematically linked texts. Nonetheless, I’ve still managed to swell this primarily pictorial instalment with all manner of reflections on my liquid topic. In part, this is due to an attempt to pin down an obscure enthusiasm, one which probably eludes final analysis. In addition, I conclude with an announcement of the premiere of my 2022 film A Spell in Fairyland which, I’m very pleased to say, will be presented by the tireless cineastes at Festival Ecrá, to who thanks are due for facilitating this film’s rise from submerged cine-obscurity into the consciousness of the floating world-mind.

František Kupka, The Beginning of Life, 1900

William Blake, Newton, 1975 - c. 1805

Jean Delville, Treasures of Satan, 1895

William Degouve de Nuncques, Black Swan, 1893

Mikalojus Konstantikas Čiurlionis, Sonata of the Sea, Allegro, 1908

For some time I’ve been fascinated with the idea of attending an exhibition centred on underwater imagery in art. To be clear, I’m not particularly interested in documentary representations of underwater scenes, wonderful as they may be, but instead in presenting imagery that has resulted from artists inspired, in part, by the world underwater: by images, descriptions, or their own experiences of it, allowing these influences to drip-feed their imaginations, before incorporating aspects of them into their art. In lieu of such an exhibition being mounted I’ve taken the liberty of beginning to assemble one of my own, guided only by my aqueous interests and an appreciation of some of the stranger areas within art. The imagery included here represents a beginning, a gathering of initial works. This work mostly springs from 19th and early 20th century culture, the weird worlds of Symbolism and Surrealism, art movements that acknowledged and celebrated the mystery-cloaked regions of the artistic imagination and drew, in part, inspiration from the liquid realm and the denizens that might be lurking there, beneath the surging waters. I imagine that, were this exhibition ever to be mounted, I’d expand its scope chronologically, including earlier works by precursors, as well as later outpourings by more recent artists. As viewers of this watery presentation, I invite you to add your own choices to this introductory selection, whilst imagining yourselves floating through the emerald chambers of this drowned museum.

Gustave Moreau, Galatée, 1880

Gustav Klimt, Philosophy, 1900-1907

Yves Tanguy, The Mood of Now, 1928

Ithell Colquhoun, Scylla, 1938

Far below, in sunless oceanic trenches, strange life stirs. On reflection, I see the imagination as aquatic, a uterine, unfixed region, where thoughts, impressions and ideas intertwine, from which art springs. This concept relates to Shakespeare, to Ariel’s song in The Tempest, which tells of drowned sailors that aren’t merely dead, but transformed by the obscure actions of magical waters, potentially to arise again, transmuted, corallised and quasi-human. John Livingstone Lowes, in his visionary, all-encompassing masterpiece on Coleridge and the poetic imagination The Road to Xanadu, aligns the artistic imagination to a depthless interiorised reservoir, into which everyday material sinks, before arising transfigured in art. I’d like to imagine that both these texts will also feature somehow as part of the show, perhaps quoted in full, in the waterproof multi-volume exhibition catalogue. As this show won’t ever exist, except in the imagination, I might as well throw in Moby-Dick too, a book that I can imagine clutching as I plunge beneath the waves.

“For here, millions of mixed shades and shadows, drowned dreams, somnambulisms, reveries; all that we call lives and souls, lie dreaming, dreaming, still.”

Herman Melville, Moby-Dick, ‘The Pacific’

Léon Spilliaert, On the Seabed with Whales, 1918

Hans Bellmer, Self-Portrait, 1942

Gustav Klimt, Jurisprudence, 1900-1907

Max Ernst, The Fugitive from Natural History, c. 1925, published 1926

Most likely, my motives for presenting this exhibition are due, in part, to me wanting to be in it, screening a film, perhaps, in some sort of adjacent underwater cinema to an audience of snorkelled spectators. Whilst the context may be impractical it is appropriate, as my films have often utilised watery imagery, from the insistent rain that soaks the scenes I create, to the successive, almost imperceptible layers of slowly moving water that I encourage my imagery to sink beneath. Until now I’ve never really pondered this particular enthusiasm, I suspect I’m both drawn and repelled by the idea of the drowned world, of things dissolving and becoming fluid. A horizontal pond surface, when filmed from above, becomes a vertical wall on the screen, suggesting, to me, an aqueous barrier erected between the world that the viewer inhabits and the regions depicted on screen. The semi-permeable membrane that David Lewis-Williams memorably describes in his neo-shamanic bible The Mind in the Cave, a barrier described as separating this world from the ancestral ghost worlds beyond, becomes, in my case, an aqueous veil. As if, beyond the enchanted undulations of water a strange world exists. Also, I like to think that the ever-present moisture undermines the fixity of the visions presented as well as, perhaps, the solidity of the screen itself. Inspiration from this approach streams, in part, from visits to holy wells and sacred springs, of looking into their tranquil depths, feeling time dissolve, mesmerised by the unrepeatable flow of mystic water; as well an ongoing fascination with half-remembered legends of magic pools, portals into which someone might pass, sinking into another dimension…

Edward Burne-Jones, The Baleful Head, 1885

Aubrey Beardsley, How Sir Bedivere cast the sword Excalibur into the water, 1893-1894

Elihu Vedder, Memory, 1870

Jean Delville, The Death of Orpheus, 1893

Toby Tatum, A Spell in Fairyland, film stills, 2022